FIREMAN’S CHAIR KNOT

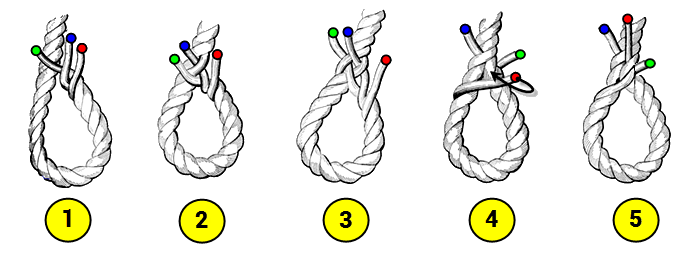

Make half hitch. Right under left. Make a second half hitch. Again right under left. Bring right hitch in front of left hitch.

Grab hitches as shown. Pull through. Make another half hitch. Put loop through. Make half hitch on the left. Put loop through. Pull ends to tighten

Use: The fireman’s chair knot is a rescue knot. There are two loops formed. One which goes under the arms; the other under the legs of person.

MAN HARNESS KNOT

The principal use of this knot is to make a loop in the middle of a rope that is being used for hauling or climbing. A man can then use the loop as a harness over his shoulder so he can put his full weight to its best use. Form an underhand loop as shown at top. Grasp the loop at (A) and lay it over the part of rope shown by the arrow. The result will be shown in the middle drawing. Now grasp the rope at (B) and draw it up under and over as shown at bottom. This forms the bight which becomes the loop for your shoulder. Draw the knot tight before using it.

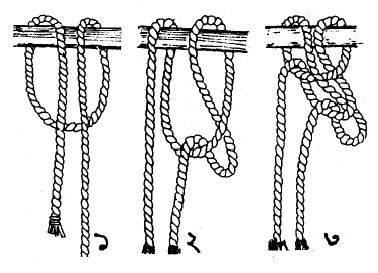

DRAW HITCH OR HIGHWAY MAN’S HITCH

The highwayman’s hitch is a type of knot. It is a quick-release, draw loop hitch popular for temporarily securing horses. There are two main features to this hitch. It can be untied with a tug of the working end, and the working and standing ends are released on the same side of the object (ex. pipe fence rail) that was tied on to.

Both of these features are desirable when dealing with horse emergencies where a panicked animal may be straining against a tied off lead rope. Because the working (free) and standing (horse) ends release on the same side of the object tied to, the free end of the rope is not whipped around behind the rail by the animal, thereby forcing the quick-release grip on the rope to be abandoned.

The knot is three bights linked through one another. To tie, begin by forming a bight behind the pole. Next, pass a bight formed from the standing part (the end that will receive tension) over the pole and through the first bight. Then, pass a bight formed from the working end over the pole and through the second bight. Pull the standing part tight to ensure that it holds. Until the knot is tightened and properly dressed the highwayman’s hitch has little holding power. When properly tied to posts or rails of approximately 2.5 – 3 inches diameter using the large diameter, compressible ropes commonly used for hose leads, it can be a remarkably secure knot.

BOWLINE ON A BITE

Tying it: The Bowline on a Bight should be easy to tie but because it is initially hard to visualize it can be confusing. This knot was actually one of the justifications for preparing all of our animations.

Uses: The Bowline on a Bight makes a secure loop in the middle of a piece of rope. It does not slip or bind. It is satisfying to start with a plain length of rope and finish with a secure safe loop in its middle. See also the Alpine Butterfly Loop.

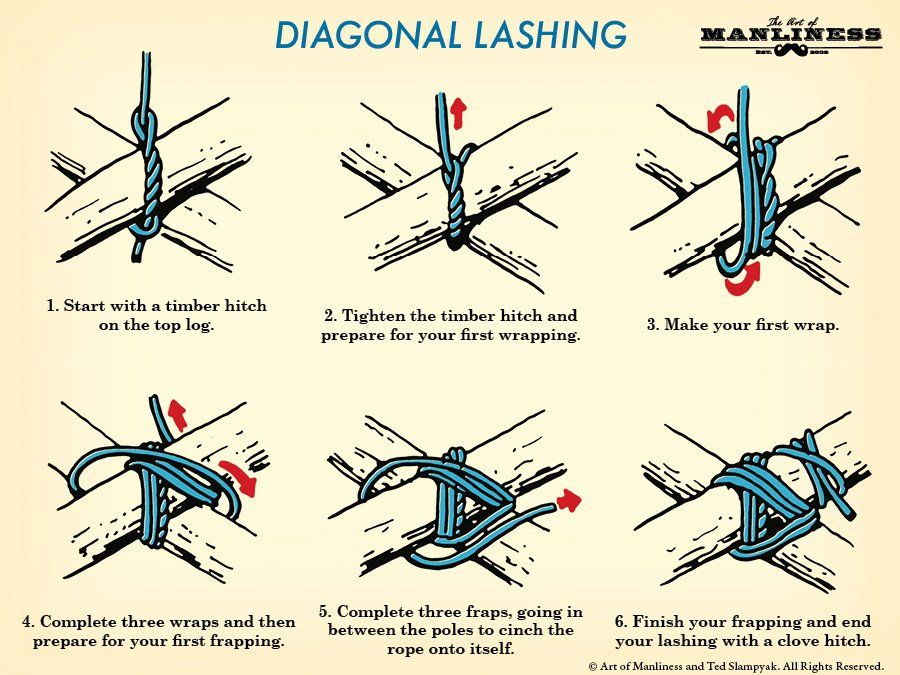

DIAGONAL LASHING

A Diagonal Lashing is used to bind two poles together that cross each other but do not touch (or are likely to be pulled apart) when their ends are lashed in place in a structure. Often used for securing diagonal braces used to hold a structure rigid.

When wooden poles are used in a lattice like structure a combination of Diagonal and Square lashings is used to hold them together.

The Diagonal Lashing can be used to bind poles that cross at an angle of between 90 to 45 degrees. If the angle between the poles is less than 45 degrees a sheer lashing should be used.

Note: If a square lashing was used to bind poles that do not touch the beginning clove hitch would pull the cross pole towards it causing unnecessary bowing of the cross pole and could also produce a force that would act along the length of the pole to which the clove hitch is tied. This could place unnecessary strain on other lashings and cause the structure to twist and fail.

Step by Step Guide

- Tie a Timber Hitch horizontally around two poles crossed diagonally. Pull tight. Take the working end around to the back of poles ready for the first turn.

- Start the wrapping turns on the opposite diagonal to the timber hitch. Pull the rope tight so that the poles contact each other. Make three full horizontal turns around both poles and over the Timber Hitch. Pull each turn tight as it is made.

- Change the direction of the turns by taking the rope behindhe poles a the bottom of the lashing then to the front of the poles at the top. Try to go around the pole when changing direction to avoid crossing the first set of wrappings diagonally.

- Make three vertical wrapping turns around the crossed poles tightening each turn before making the next one. Be sure to keep them parallel.

- Tighten the lashing with a frapping turn by going past and around one of the poles and then threading the rope alternately behind then in front of each pole. This will help to secure the lashing.

- Make two more frapping turns, pulling each one tight as it is completed.

- End the lashing with a clove hitch by taking the first half hitch of the clove hitch by going past and then around one of the poles. Lock the half hitch tight against the lashing by working it tight and pulling it from below.

- Take a second half hitch around the pole and work it tight against the first so that the clove hitch is locked tight against the lashing.

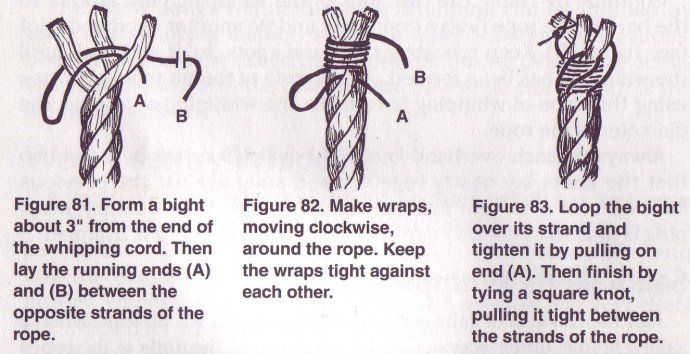

WHIPPING

WEST COUNTRY WHIPPING:-

Pass the twine round the rope and tie an overhand knot. Repeat behind the rope and tie another. Continue making overhand knots in front and behind to reach the diameter of the rope. Finish with a square (reef) knot. Or add more overhand knots, thread the ends through the rope and trim them.Animation To photograph this animation, large diameter cord was used. When tied with normal whipping twine, this makes a satisfactory, neat whipping.

Uses: The West Country Whipping (ABOK # 3458, p 548) must be the easiest whipping to teach and learn – merely a series of overhand knots completed with a reef knot! No equipment is required except the whipping twine. At best, it is only a reasonably satisfactory way of securing the end of a rope. The final reef knot can shake loose followed by each overhand knot. However, it does fail slowly – the overhand knots work their way loose in succession and, as each one loosens, an opportunity is presented to procrastinate: tie another reef knot and put off having to whip the end properly with a better whipping.

Techniques: There are several variations of this whipping:

- Where to Start: When whipping a rope’s end it seems natural to wind the twine outwards towards the end. There is, however, an advantage in starting at the end and winding the twine inwards: when the whipping is completed, the ends can be pulled through the body of the rope to prevent them unravelling.

- Reef Knot: The classic description completes this whipping with a reef knot with the ends trimmed. A heavily used rope will shake this reef loose. If a needle is available it is worth burying the ends by pulling them through the rope.

- Multiple Reefs: The West Country can be completed with a stack of reef knots but this leaves an unsightly tail. If a needle is available, this string of reefs can be pulled through the rope to bury it.

- Start with a Constrictor: A quick way to start the West Country is to drop a Constrictor Knot on the end before tying overhand knots. This has the advantage of quickly gaining very secure control of the rope’s end. It also leaves a fairly reliable last defense if the whipping comes undone.

SAILORS WHIPPING:-

With the end taped or burned, lay the whipping twine aginst the rope and tightly wind the twine round until the twine is secured – usually eight to ten turns. Make a loop and wind the loop round the rope and the twine – another eight to ten turns. Pull tight, & cut the ends off close to the rope.Animation To photograph this animation, large diameter cord was used and only a few turns were applied. When tied with normal whipping twine, many more turns are used.

Uses: The Sailor’s Whipping (ABOK # 3443, p 546) is probably regarded as the classic simple whipping. It can be tied with no needle and when tied tightly provides a very satisfactory, neat end to a rope. With a little practice, and the appropriate size of whipping twine, the appearance is of a cylinder of stacked turns and the ends are invisible.

Techniques: There are several variations of this whipping:

- Using a Bight for the Finish: The second half of the whipping can be wrapped round a bight formed with the first short end. The final end is then inserted into this bight which is then pulled through.

- Round Turns Between the Ends: After the first end is securely contained by 8 – 10 turns and trimmed, several turns are often laid before the final end is wrapped in. This separates the exit points for the ends and makes it easier to conceal them.

SPLICING

EYE SPLICE:-

Unravel enough for 5 tucks. Tape the rope. Arrange strands. Pass center one under a standing strand. Pass lower one under lower adjacent standing strand. Pass the upper strand under the upper adjacent standing strand. Repeat this process with the center strand, the lower strand, and the upper strand. Continue to create five complete sets of tucks. Pull tight.Important: The Eye Splice and its variants are well described by Ashley (ABOK # 2725, p 445). Modern synthetic materials, however, tend to be slippery and, now, a minimum offive complete “tucks” is required. For mooring, tow lines, and other long term or critical applications, seven tucks are recommended. The animation above only shows the threading of two complete tucks with the final image showing four tucks finished and tightened.

Esssential Preparation: Secure the end of each strand by heat, tape or whipping twine. Measure the length to be unraveled and secure the rope at that length with tape or twine. The correct length to unravel is about 3 times the diameter per “tuck”, i.e., for five tucks in half inch diameter rope, leave the free strands at least 7.5 inches long; and for seven tucks at least 10.5 inches. Create the required size of loop and mark the rope. In the illustration above the mark would be on the blue standing end where the first red tuck is to be threaded.

Technique: The illustration above shows two complete tucks being created. In tightly laid or large diameter rope, it may be difficult or impossible to pass each strand under the standing strand without a tool. The following have all worked for me under different circumstances.

Merely wrapping each end in masking tape can provide you with a “spike” to feed under the standing end. Alternatively, use a suitable spike to open up a standing strand. It may stay open long enough for the strand to be threaded.

I have used many different spikes including marlin spikes, pencils, pens, and needle nosed pliers. Finally, the best tool is undoubtedly a fid, a spiked aluminum bar with a hollow end, which opens up the standing strand. You then push the strand through inserted in the tail of the fid.

Structure As in weaving, each of the strands is passed first under and then over alternate standing strands. In the process, the free ends tend to untwist and become untidy. Handle each strand with care to retain its original twist: after each strand is threaded, twist it to try to restore its original fimness – at least for the first two or three tucks.

Holding the Rope: Having prepared the ends and chosen which strand to thread where, it is then all too easy to get confused after it is threaded. Hold the other two tails in your hand, one each side of the rope; they will then be in the correct place when you want to choose an end to thread next (picture on left).

Finishing the Splice: If the ends have been cut to the correct length, they will be used up in the splice. If they are a little too long, it is usually far less trouble to make another tuck than to cut them and reburn them to stop them unraveling. The burned ends are usually slightly larger than the strand and this provides some of the security of the splice.

Tapering the tails: It used to be fashionable to gradually thin the strands for an additional few tucks. In tarred hemp this made a very elegant tapered splice. Modern rope is sufficiently slippery to mean that the tapered tails tend to get dislodged and make the splice look very untidy. True tapering of individual strands is rarely done now and should probably never be attempted by amateur, occasional, splicers.

Alternative Taper: After sufficent tucks have been made for strength, cut and burn one stand and then continue the splice with remaining two strands. Cut and burn one more and splice the remaining strand before cutting and burning it too.

SHORT SPLICE:-

Begin by unlaying (untwisting) the ropes a few turns. If the rope is large, make temporary whippings on the ends of the strands.

- Alternate the strands of the two ropes.

- Tie strands down to prevent more unlaying.

- Tuck strand 1 over an opposing strand and under the next strand.

- Tuck of strand 2 goes over strand 5, under the second, and out between the second and third.

- Repeat operation with strands 1 and 3 from same rope end.

- Remove tie and repeat operation on other rope end. Make two or more tucks for each strand. Then roll the tucks and cut off ends.

You can smooth the splice by rolling it under your foot on the floor.

BACK SPLICE:-

Form a Crown Knot by tucking each strand over its neighbor and back down beside the standing end. Splice each strand into the rope by passing it over and under alternate strands in the standing end. Three complete tucks – two more than the one shown here – are sufficient.

Uses: The Back Splice (ABOK # 2813, p 462) provides a secure method of preventing the end of a rope from fraying.

Structure: The back splice consists of two parts: a Crown (on right) to redirect the strands back towards the standing end; and the braiding to tuck the ends into the standing strands. About three complete “tucks” are sufficient as no load is applied to a back splice.

Disadvantages: It makes a bulky end to a rope and usually prevents the rope’s end from passing though blocks and pulleys. For most purposes, a whipping is preferred – see Sailmakers, Sailors, or West Country whipping.

Advantages: No additional tools or equipment are required and it is easily learned and quickly tied.

Splice the Mainbrace: History of Grog: Ashley’s (Splicing Section p 461), explains that Splicing the Mainbrace meant serving Grog to all hands at the completion of some particularly arduous labor. He omits the explanation that Grog was named after its inventor Admiral Edward “Old Grog” Vernon so named for the admiral’s waterproof Grogam coat (sometimes spelled Grogram). Grogam (or Grogram) is defined as a thick material which was a combination of silk, mohair and wool often stiffened with gum.